Cycling Aerodynamics: Wider tires and Rims examined in Engineering Detail

Introduction

This post will cover the science and marketing relating to wider tires and rims, there is a general push by the bike wheel manufacturers and to an extent tire suppliers to push wider rims and tires. The argument is they are faster, puncture less and produce more comfort. This post is worth reading in conjunction with a topic on modern real world cycling aerodynamics

Aerodynamic Losses

This is perhaps the most contentious subject and it is based on aerodynamics that many would argue are not applicable for a bicycle wheel and tire combination.

The basic formula that many use for determining drag is an application of Bernoulli’s with dynamic pressure and a non dimensional coefficient for drag Cd. This formula is perfectly acceptable when flow is considered to be steady state (parallel with little deviation in incidence angle or 2D velocity).

\begin{equation}

D = C_{D} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \sigma V^{2} \cdot A

\end{equation} If this is broken down into the fundamental terms and compared between two rim and tyre combinations (23mm and 30mm), an indicative conclusion can be garnered. In this general equation, the fixed terms are the density and the rider velocity. The parameters that vary between the wheel sets are the A term (wetted area) and the Cd (Drag coefficient. The Cd and A terms are functions of wheel geometry and this is where the math starts to get more involved.

Using an ISO chart for raddii sizes, this gives the following

| Rim | Tire | Rim (ISO Size) | Tire (mm) W | Combined Tire and Rim Diameter (mm) D | Rolling Circumference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 700c/29er | 23 mm | 622 | 23.00 | 668.00 | 2098.58 |

| 700c/29er | 25 mm | 622 | 25.00 | 672.00 | 2111.15 |

| 700c/29er | 28 mm | 622 | 28.00 | 678.00 | 2130.00 |

| 700c/29er | 30 mm | 622 | 30.00 | 682.00 | 2142.57 |

Considering the two popular combinations, the previous favorite (23mm) and the new favorite (30mm), there is a stark difference in wetted area. This is a simple formula

\begin{equation}

A = D \cdot W

\end{equation} which for these two equations gives

\begin{equation}

A_{23mm } = 668 \cdot 23 = 15364 \cdot mm^{2}

\end{equation}

\begin{equation}

A_{30mm} = 682 \cdot 30 = 20460 \cdot mm^{2}

\end{equation}

The difference in purely wetted area between a 30mm tire and rim combo is a staggering 33%. This is due to a combination of not only increased width but also height. Henceforth, a 30mm tire and rim combo would require the Cd term in equation (1) to be ~33% lower to “break even” aerodynamically.

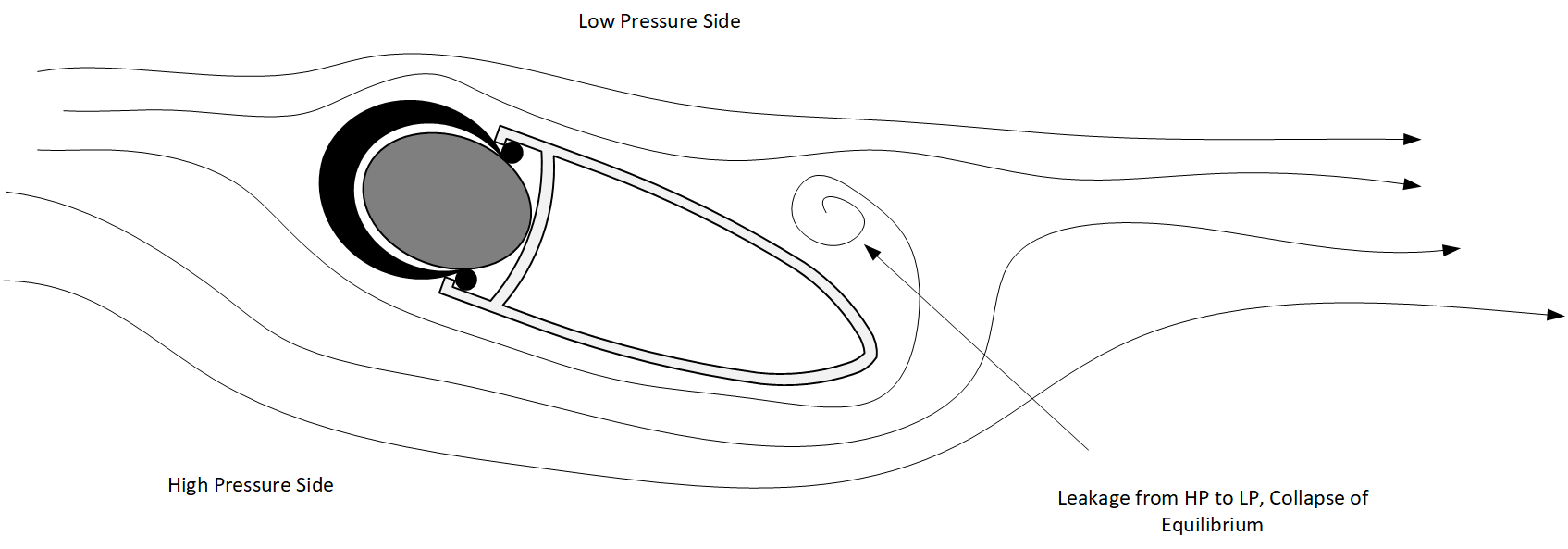

The Cd for bike wheels is almost entirely determined by the width and depth of the tire and rim combination. Narrower wheels with deeper rims are more aerodynamic. In this mathematical case, the width is fixed so the only variable that can be changed is the depth. A graph based on wind tunnel data shows a clear correlation between depth and Cd (*in this case proven power is equated to Cd). The absolute values should not be considered accurate as many variables can influence the absolute reading but the relative readings are valid as they were conducted in the same tunnel and other variables remained relatively constant.

At 30km/h the trend line equation is shown below. Very loosely, every mm of rim depth is worth about 0.25W reduction in power

\begin{equation}

Power_{30km/h} = -0.2533 \cdot RimDepth + 199.16

\end{equation}At 50km/h the trend line equation is shown below. At this speed, every mm of rim depth is worth 0.84W of power reduction

\begin{equation}

Power _{50km/h} = -0.8397\cdot RimDepth + 641.71

\end{equation}The graphs above show clearly (using verified empirical data) that the increase of width in a wheel and rim combination can only be overcome with an increase in rim depth. Effectively the increase in wetted area can only be mitigated by improving Cd – to improve Cd requires an increase in rim depth. It is possible to add in some aerodynamic “trick” features but their effectiveness is small compared to rim depth with is by far the dominant parameter.

The base data is Dnitriev derived and can be found here 30km/h and 50km/h

Wider Tires have Lower Rolling Resistance

An often cited comment from various internet forums is that wider tires have a lower rolling resistance. This is true providing one key variable is maintained, they must be pumped to the same pressure.

For absolute minimal rolling resistance, an infinitesimally small contact patch (and thus infinite contact stress) would be required and this is the subject of Hertzian contact mechanics. The limitation with total application of Hertzian mechanics to this problem is the fact that road surfaces are rarely perfectly smooth and the objects involved are not sufficiently stiff enough.

Rolling resistance is mathematically quoted as a coefficient Crr. It is a dimensionless and unitless value. Some typical Crr’s are shown below.

INSERT TABLE

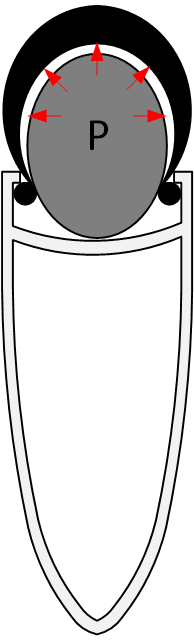

In practice the maximum pressure and even reasonable working pressure is limited by hoop stresses in the radial fibres of the tire and strength of the hook on clinchers. Hoop stress is a circumferential stress that is present on pressure vessels (typically cylinders eg. Coke cans and Aircraft fuselages) at the walls of the pressure containment object.

Mathematically, the formula for thin walled pressure vessel hoop stress is

\begin{equation}

\sigma _{hoop} = \frac{P\cdot D}{2 \cdot t}

\end{equation} Where P = Internal Pressure, D = Diameter, t = Wall Thickness

There is also an axial or longitudinal component, this is generally ignored for this type of analysis as the stress is half of the hoop component.

\begin{equation}

\sigma _{axial} = \frac{P\cdot D}{4 \cdot t}

\end{equation} For a more thorough analysis, a mohr’s circle of stress would be required but for the purposes of this blog post, the axial stress will be ignored because it is half of the stress of the hoop component (denominator 4t as opposed to 2t).

Rearranging, the formula, the ramifications are quite clear. An increase in tire width will result in a linear reduction in maximum tire pressure

\begin{equation}

P= \frac{\sigma _{hoop}\cdot2 \cdot t} { D}

\end{equation} The relationship between maximum tire pressure and tire width is inverse so the delta will get smaller as the tire width increases, changes. eg. it only takes 1mm of differential to produce a 0.5bar pressure drop between 22mm and 23mm but it requires 3mm of differential to get the same drop at 37mm of tire width. In short, a narrower tire allows a higher pressure with lower rolling resistance and simultaneously a lighter tire which allows faster acceleration.

If a rider runs their tires at the maximum allowable pressure, a narrower tire will always have lower rolling resistance – this is due to the nature of hoop stress.

Vibration or Suspension Losses

Vibration or suspension losses come in two primary forms. There is a loss caused from energy of the rider being absorbed (moving them up and down), deformation and a loss of traction (or a slippage loss). These losses are affected by:

- Rider Weight

- Rider horizontal position with reference to the front and rear wheels

- Tire width

- Handlebar position (stem)

- Spoke pattern, tension

- Wheel stiffness

- Wheelbase of the bike

- headtube angle

The VERTICAL energy loss with regards a bike in this regard is disputed. Theoretically, the energy lost (technically transferred) will be the same between a narrow tire and a wider tire and this is due to the basic equation of energy transfer being a product of the excitation force and the displacement. In reality, the perceived loss is due to the bounce or poor NVH which makes it less “comfortable” and more difficult to pedal.

Mathematically, there is a clear difference between the damping and spring constant of a wide tire against a narrow tire. Tire constructions are generally unchanged between the sizes and the disparity is a result of the tire pressure differentials and volume of air contained within the assembly.

Plenty of simulations can be run to predict the difference between a wider tire and a narrower tire in terms of response. The general thought is that most paved road surfaces are not bumpy enough to provide a tangible suspension difference between a wider tire and a narrower tire. The suspension component could (for instance) be moved to the seat rails and the final outcome would not present a hugely different outcome. The exception to this is if the rider is extremely heavy. In this scenario a wider tire at a lower pressure would likely result in a much improved traction and comfort. If this applied at a complete bike level, very few riders would actually have any advantage from going from 23mm to 28mm on the FRONT of their bike, there is essentially insufficient weight on the front axle for a tangible difference.

The caveats are quite extensive as these losses are heavily influenced by bike geometry. A pure analysis of rider vertical movement is not realistic but it is often used by wheel companies to sell the advantage of “wider wheels”. For example, Moving the rider handlebars (and thus shifting their weight) is likely to have more of an effect than a change in tire size.

Is wetted area that big of a deal here? In low speed aerodynamics pressure drag not skin friction is the dominant driver of drag.

Also what about impedance losses in the casing itself?

It will all add up. Especially the difference.

I’m curious regarding your wind tunnel/turbulent regime testing. Are you able to share your procedure for both curious to see how you’re going about doing these measurements.

Also I’m curious how wheels/frames behave in transient environments where you have small shifts in yaw angle due to steering inputs or small sub 1 mph changes in wind conditions. I almost want to get a nice 3D scanner to scan some of my wheels and do some modeling.

Thanks, very interesting post. Some notes:

– I checked my bikes with 23mm, 25mm and 28mm tires, the combined tire and rim diameter on all of them seemed to be around 682mm. I only used a tape measure but that would not introduce a 10mm error. The respective inner rim widths are 17mm, 18mm and 20mm.

– “If a rider runs their tire at the maximum allowable pressure, a narrower tire will always have lower rolling resistance” – true in theory, but it appears that not even world tour teams run at maximum pressure. I am sure that they would if it actually made them faster long-term, e.g. in long races or stage races. By the way, the max indicated pressure for GP5000 clinchers is 8.5 bar at 25mm and 8 bar at 28mm width.

– I don’t think wheel manufacturers claim that wider tires have lower rolling resistance in perfect conditions, the argument was about imperfect real-world road surfaces where tire pressure would be sub-maximal. Silca recommend first choosing a tire for the given conditions and then finding a matching wheel and bike. Zipp and DT Swiss claim that when setting up a wider and a narrower tire for comparable levels of comfort (“same size of contact patch”), the contact patch shapes will be different. The narrower tire’s patch will be longer (in direction of rotation), leading to more deformation and therefore more energy loss. I have no idea if this is true but it should be relatively easy to measure the effect in a lab. See https://www.dtswiss.com/en/wheels/wheels-technology/aero-plus-technology

– Additionally, the risk of pinch flats should be lower when running wider tires at the same level of comfort.

It feels like the easy answer here is to simply perform rolldown tests with various tires and wheel combinations or otherwise perform some sort of real-world comparison (for example, with the popular “chung method”) rather than simply relying on these types of theoretical modeling results. Yes, the real world is messy, but it’s also where we all ride our bikes.

I have found the Chung method to not be accurate because it is skewed by conditions such as street furniture. The rolling drag presented here is an empirical measurement as is the wheel data.

Thanks. It’s really cool that you put common sense to formula. There is often much discussion about what is fastest. But the majority of people believe more in advertising than in physics.

Hi, thank you for the post.

I would like to know if there is a limitation of the tire width vs inner rim width?

For example, I’m now running a 19mm inner width rim with 25C tubeless tire, is it ok for me to change a same brand 23C tubeless tire for better aero/weight? Or 19mm is too wide for 23C

Given that a cyclist wants to ride a wide tire (e.g. 28mm measured width), what is the optimal rim for that tire at 30 or 50 km/h, all things considered including weight? Probably not a narrow shallow rim, and possibly not a wide super deep rim. What hits the sweet spot?

you’d need about 4 times that to get re attachment, so you’d be looking around ~120mm rim

Hi there watching this I realized that just made a mistake buying my wheels, I bought a pair of elitewheels 50mm deep 15.6 internal width and 25mm external… I usually ride 28mm tyres on my older alloy rims, so using 28mm on this ones will kill any aero gains from the wheel right? Even 25mm will fall short? Or 25mm front and 28mm on the back is a good combination? I really didn’t want to go to the 23mm has it is an outdated width and uncomfortable… Did I made a mistake buying this sized wheels on 2023 when there are far way wider rims internally on the market? Thanks. Gustavo

Tyre Rubber hysteresis needs consideration. I also think all your analysis assumes 100% elasticity, i.e all storage, no loss.

Hi Hambini!

I wish I knew your real name…

So, I’d like to ask to you to think about the following trend and maybe post dome about it: optimanl tyre width. My current state of mind is that the narrower the better as long as I have the right the pressure and as long as I can stand it (as a rider withstanding the road impurities).

The people in my bicycle club have been wondering what to do when it comes to tyres width. Latest brand new aero bikes come with standard standard 28mm tyre nowadays. I responded to them that the premise of bike manufacturer was to deploy the tubleless technology. In order to do so, they had to increase the tyre width to make the tyre and rim tolerance more feasible and manageable on an industrial perspective.

I am observing on a wide scale that bike frame manufacturers had to increase the frame width on the front end of the bike to accomodate wider tyres. So, as would ‘Paul Lew’ frame it, it would come down to the dilemna between ‘high grag’ versus ‘low lift’ as is the analogy with the wheel rim profile, while eac of them has their own draw back but similar average aerodynamics gain.

Can you calculate any drag grain with the latest generation of frame (e.g Giant 2021 frame, specialized venge pro 2022, canymon aeroroad 2021) combined with 28mm tyres?

Thanks a lot

Hicham

A French Moroccan Dude with a lot of Physics and Biking in his limited avg head!

Hey there Hambini- thanks for the writeup. I’m wondering if there might be any downstream gains to wider tyres breaking a wider a slice of air for the comparatively wider downtube to pass through. I imagine any potential gain here would be counteracted by losses in the wheel air passing underneath the frame.

I’m also wondering how a downtube with a larger gap like a supersix would compare in this setting vs say the cutout on the new s5. I would have imagined that such a cutout would be designed and optimised for the airflow of a specific tyre and rim width, but the extremely large 34mm clearance flies in the face of that.

Cheers,

Andrew

Generally, most aerodynamicists will try to prevent a mix of flows until the air has exited the frame of the object – in this case behind the bike and rider. This is generally accomplished by having solid surfaces through which air cannot penetrate. The use of large gaps tends to cause mixing and thus turbulence generation. Sometimes gaps can work, but it is unlikely to work across a massive speed range. Gapless aerodynamics works at any speed. The use of a wider tyre to try and cut a hole for anything behind it doesn’t generally work because air starts to recover as soon as it leaves the trailing edge of the wheel. It would work if the front wheel was (for example) a disc but the hole cutout kills it. I hope that helps

Thanks a bunch- very much appreciated

Very interesting… I’m a little slower rider doing rando. wonder if it makes sense to get aero wheels/ tire combo vs my box rims. Average 14mph, that’s often on hilly roads. Rides typically are 200k, 300k, 400k, occasional 600k. So I’m on the bike awhile. Aero rims help? Gp5000s, H Plus Son tb14 23mm rims.. Just wondering..

What is you opinon on 3T Mercurio 60 LTD, they have some different solution, legit or not ?

https://pezcyclingnews.com/latestnews/3t-mercurio-60-limited-wheels-can-the-old-barstempost-masters-make-a-wheel/

I find this an interesting spoke solution. This enables them to build almost any rim profile at the “normal spoke position” in the rim, but they came with a relatively blunt rim profile nonetheless (after testing in a wind tunnel they claim).

Do you have an idea how the inertia is influenced? Weight in the rim is reduced by having no nipples, but the carbon holding construction has weight too and is further from the hub and closer to the tyre. The weight is for a tub, who always ride super nice and supple (no stiff tyre-sidewalls) and are more safe (tyre cannot blow off or roll off because it is attached/ glued on).

I find it very strange that they find it unnecessary to cover the big spoke holes. I hope that is not of wanting you to show off their spoke holes purely for marketing reasons, or because they have no good solution for it. That makes me wonder if they investigated rotational drag (25% of the bike/wheels resistance is rotational drag according tot DT Swiss and the rotational drag of the front wheel should contribute 8% x 25% = 2% tot total drag). Personally I would take some electrical tape and tape off the spoke holes.

Lateral stiffness being on par with other wheels in the test makes me wonder how that is defined. I would suspect the amount of flex changes differently with the amount of force.

Example: I have a special car road tyre/rim combination, lateral flex is much more because I run (have to run) half the normal air pressure with this combination. Cars passing by sway the car sideways MUCH more easily and further. Yet this rim/tyre/pressure combination is considered much stiffer and more comfortable, and that is because much of necessary damping is there but it stops sooner. The normal combo sways less sideways, but it keeps swaying giving a wanky feeling. But mine feel comfortable and stiff at the same time; because sideways forces are allowed more but the sideways flex stops sooner and does not continue almost indefinitely in sideways distance.

So there could be some more data published on lateral stiffness and that might be interesting. Like a curve of sideways force versus side deflection of wheelsets.

Sideways stiffness is also affected a lot with tyre width and pressure, just take high speed photo’s of sprinting cyclists; those with wider tyres (26mm versus 28mm) and lower pressure sway a lot more sideways because the tyre flexes more sideways, and a wider tyre can also flex more sideways even or especially tubeless tyres. Who knows, perhaps the benefit of wider tubeless tyres at lower pressure is in part caused by absorbing too high sideways forces.

The sideways swaying must not be too excessive, because when riding wider tires the rider prefers wider rims also, which counteract sideways swaying a bit.

There is so much not understood or not discussed (that is why I like Hambini, because he discusses it). As if scientists are more interested in distant star systems than these phenomena or more interested in extremely rare diseases instead of investigating for example the cause kidney stones which are very common and reported as being very painful.

What is the normal radial stiffness and damping coefficient associated with a mountain bike tire?

There is no “normal” radial stiffness or damping coefficient in MTB tyres because all experienced riders in XC ride between 1,0 bar (sometimes even lower) and 1,4 bar (mostly just on narrower MTB tyres). At those pressures which are custom determined by everyone and specifically adjusted for every terrain, weather and race type there is a totally individual custom radial stiffness and damping.

Generally in MTB riders want stiff wheels so they can determine their factors by internal rim-with and tire pressure. But wheel manufacturers also do marketing with “compliant wheels” nowadays. A lot of this “compliance” is marketing coming from using ever thinner rim height and thinner and less spokes to save weight and selling compliance as a need in stead of a negative downside of weight savings. Although some compliance keeps a wheel from breaking.

The most expensive DT MTB wheels have gone from 28 spokes per wheel to 24, which does not seem like a smart move seeing Scott promoting big interconnected carbon wheels in which rim, BIG spokes and bub are made from one piece of carbon for stiffness. I do not know which is better because those wheels are so expensive that almost nobody can buy the newest versions of those wheels just to compare them side by side. Or they are sponsored and need to sing the gospel of their sponsor to the public and hide what they true thoughts are to the public (that feedback is purely for the sponsor). Many oldtimers prefer rims with more spokes, like 32 spokes, because to them stiffness is more important than weight to achieve high speeds.

Very little is published in MTB as to what is better. Although most riders prefer lighter wheels, which in part comes from the fact that more expensive wheels, built with higher quality components and more care, are lighter. Most companies advertise the wheels with primarily with weight and lighter as better (and more expensive). More expensive must be better. So lighter must be better. In road-cycling once 19mm tyres were considered the best and everyone wanted even narrower ones, and now look at this article by Hambini and the current trend…

Thank you! This was presented in a way that you do not need to be an engineer to understand. The most scientific and coherent explanation of Tim and the signs on a bicycle.

One element is missing: nipples (especially when using aero spokes) and rotational drag.

Deeper rims with the aerodynamically right tyres reduce aero drag; which makes rotational drag a higher percentage of remaining total drag. So bladed aero spokes and smaller or hidden nipples become a bigger factor. Spokes get a lot of attention and discussion. But spoke nipples are the “part of the spoke or part of the hub/rim connection” which is the bulkiest (widest) has the worst shape (square) and has the highest velocity because the spoke at the top of the wheel near the rim has almost double the velocity of the bicycle and is moving against the riding direction. The spoke at the bottom of the rim is standing still on the pavement. With aero drag rising non linear (exponentially) with speed this matters.

12mm nipples should be more aero than 14mm or 16mm nipples. Hidden nipples place the nipple inside the wheel, taking them completely out of the aero equation.

Hidden nipples also shorten the part of the spoke that is not bladed, because for internal nipples the spoke goes deeper into the rim and therefore a tiny bit longer part of the spoke is inside the rim (you will need slightly longer spokes for internal nipples). The bladed part gets closer to the rim and that should also be more aero than the otherwise longer round (non-bladed) part near the nipple.

This should result in aero gains, is it not? But how much? And how much does that change when the rim gets deeper let us say from 40mm deep we increase rim depth to 75mm or 80mm.

And is the effect of this the same in the front and rear wheel?

And what about wave pattern rims like Princeton and Zipp have (Zip has both sawtooth and wave shape). More manufacturers offer the “wave shape” but Princeton and Zipp are most known for it because they are in a lawsuit about who invented this and could own rights to that design.

The spoke is on the top of the wave and between spokes the wheel is 5mm “shallower or less deep”.

The exposed part of the spoke gets 5mm shorter by that, and the nipple or round part near the rim gets closer to the hub, reducing the forward speed (and aero by the square amount) when riding compared to a standard rim that is round on the inside.

These wave shapes claim to be more aero (shorter nipples) while maintaining the side windgust stability of the more shallow rim (and they claim even more but those extra’s could be marketing).

I am planning for this reason a 60/65 wave shape front rim combined with a 75/80 wave shape rear rim; and the part I am thinking of is internal or external nipples.

External nipples allowing for a tubeless rim without rim tape (5-15 grams per rim), shorter spokes and nipples closer tot the wheel center: all reducing weight and inertia of the wheel. This wave shape is mechanically stronger/stabler so adds no weight on its own compared to the weight of a “standard round rim”.

It would be nice to hear some thoughts about this, as nobody seems to touch this subject. At least nobody dares to go deeper into this and nobody dares to guess what watts saved could be at say 50km/hour or above.

Anyone any thoughts on this?

What could bladed spokes (more aero) contribute? CX-ray being a popular one, or even broader carbon spokes.

What could tinier or hidden spoke nipples contribute?

What could fancy rim shapes contribute?

Silca claims a valve adon to make the valve more aero already gives a huge aero benefit. Maketing or possible real?

As tyre/rim combinations get better matched, rims go from practically boxed rims to deeper rims, more aero helmet, better rider position; all adds up into speed increases WHICH IN TURN at the higher speeds make aero more important and more effective.

Especially as cruising speed, chasing to get to a group or the final sprint goes above 50 kilometers per hour (above 32 miles/hour) lots of ignored / overseen things get more important.

As sprinting speeds regularly reach 60km/hour (38 mph) overseen aero gains could really count or add-up.

Has nobody an opinion or guess?